The paramedics called the orange backboard they used to scrape up my brother their “pavement spatula.” I heard the fat one say that, as he hitched black cargo pants up to where his stomach hung free from his polo. That’s what stuck with me from the day my brother, Simon, had been thrown through the windshield of our family’s Suburban. I don’t remember what I had seen when I inched out onto the shoulder to make sense of the shredded form on the road – thank God for smaller favors. Instead, I remember a fat man, his hairy stomach, and his pavement spatula.

At twenty-one, I’ve earned my EMT license and am onboard at Baker Valley Ambulance out of Bradford, Vermont. Frankly they’ll take anyone with a pulse up here, just to drive the paramedics around. For $18.13 an hour, I’m happy to oblige. It’s enough to move out of Mom’s place and its cat piss must.

Mom had been wary around my decision to enroll in an EMT program around shifts at Green Mountain Rehab, where I’d worked the kitchens (i.e., the microwaves).

“Derek, does this have something to do with Simon?” she had asked, her voice pinched. I told her no, and at the time I think I believed that.

Dad hadn’t asked me a thing about it. He didn’t talk about Simon. Ever. He had been behind the wheel when the SUV had slid off I‑93 and into the front end of a guardrail.

#

On one of my first ridealongs on the ambulance, we’re dispatched to a self-inflicted GSW, apparent suicide.

“You can sit this one out,” says Marge, my paramedic preceptor, as we pull up on scene.

I shake my head. “I’ll be alright.”

It’s different than the movies. It’s difficult to find the entry wound – Marge needs to push aside the woman’s heavy breasts to expose a red dot hardly bigger than a dime.

I had been unsure of what to expect, especially after what Mom had said, worried that my mind would dredge up something long buried. But I don’t feel much of anything, to be honest. There seems some kind of glaze between me and tragedy ahead. My brain refutes the reality of my patient, sees the splotchy moles on her chin not as the product of a lifetime shunning SPF, but simply as texture. I push myself to internalize that someone had once been in this body, but the idea beads up on the outside of my brain, water on wax.

I quickly built a base of high acuity calls: an overdose I’d gotten to Narcan, some guy who’d lacerated his arm on a metal grinder, a stroke victim, who’d been collapsed in his backyard for God-knew-how-long, who’d soiled his jeans and vomited on the front of his sweater.

But none of those calls had seemed real in the moment. My body had acted, my mind had worked to problem solve, but I had watched from a distance.

#

The weird shit starts in January, about four months into my employment.

A 911 medical call brings Marge and me to 215 Old Post Road, Orford NH for Mr. Peterson, a frequent flier with Baker Valley Ambulance. Mr. Peterson has Stage IV lung cancer that’s turned him into a skeleton of a man, hollow eyes, grey skin, arms so thin I use the pediatric blood pressure cuff to get an accurate reading. He’s one foot in the grave already, and today, he’s coughing up blood.

“I couldn’t sleep last night,” says Mr. Peterson, en route to the hospital. Marge is letting me do patient care.

“Not like I can do anything for him,” she had shrugged, ripping a mango-scented hit off her vape.

I hook Mr. Peterson up to a nasal cannula at 4L and take a quick 12-Lead before we head out, just to do my due diligence. Now there’s nothing left to do but drive the thirty minutes to the Dartmouth-Hitchcock ED.

“The coughing kept you up?” I click open my pen and scrawl a note in the ‘History’ section of the drop-sheet.

“The coughing too I s’pose,” says Mr. Peterson. As if to demonstrate, he hacks into his handkerchief. It’s hard to tell if he brought up any blood, the cloth is already smeared. “Mostly it was the bells.”

“Bells?” I ask. 215 Old Post Road is way back on some chewed up dirt roads. There isn’t any nearby church, or really a nearby anything as far as I know.

“They were in my head,” he says. “I was a firefighter. Forty-two years, down in Bradford. When one of ours passes, they ring the bells all day long. Last night I heard ‘em going and going.” He fixes me with a resigned stare. “They were chiming for me.”

I would later find out Mr. Peterson had torn his esophagus. It was serious enough that he needed a surgical repair, but there was some complication – a thrown clot or something – and Mr. Peterson never woke up.

After the end of my shift on the day Mr. Peterson dies, I drive over to the firehouse. The bells are ringing a steady dirge – clang, clang, clang.

That night, I can’t sleep. That’s unusual for me – I’m the kind of guy that runs a chronic sleep debt, no matter how many hours I get. When my head hits the pillow, I’m out. Tonight, I roll from side to side. I hear those bells clanging their somber song, wedged in my mind like a stubborn pebble.

#

Early in my orientation at Baker Valley Ambulance, Marge warned me that everybody gets that First Call, and it’s never pretty.

The tone for mine drops at 2:47 in the morning. It’s an Advanced Life Support call, eighteen-year-old male, suspected OD. Ripped halfway from a REM cycle, one boot on before I realize I still need my pants, I pause to pay attention to dispatch. Fire is already on scene, CPR in progress.

The ALS truck is stuck down in ED purgatory, waiting to drop off their stable A‑fib patient. Myself and my similarly wet-behind-the-ears partner, Cheyenne are both measly EMT-Basics, running a Basic Life Support truck. I sign on over the radio. Cheyenne drives, lights and sirens. We aren’t entirely sure where we’re going.

This call is different.

The details are jarring, sharp, my mind thrown and rattled every time I spot something new. Collision.

The dad’s outside, yelling, and hurling clay turtles from the garden against the garage door. The driveway is littered with ceramic debris, the garage door hardly dented. Futile. The mom’s on the upstairs landing, clutching the railing and screaming wordless anguish that echoes off the drywall. She screams the whole time. I’ll still hear it, long after we clear the scene. Days after.

I’m scrambling to get our monitor hooked up to Fire’s pads – my hands shake so bad I struggle to hit the big power button. Once it’s on, I keep pushing the wrong arrows to navigate. My attention isn’t fixed to my patient like it usually is. A good portion is listening to that woman scream. She’s getting hoarse, but still loud as all hell. I worry she’ll tear something.

The kid’s in asystole. His lips are purple, his cheeks a waxy yellow, his eyes glazed and pinpoint. Fire had given Narcan, but no one has started bagging. I go to the airway as Cheyenne takes over compressions, and the patient’s mouth is filled with blood. I start suctioning – some of my autopilot is back – but the blood doesn’t drain and then it’s spilling all over the patient, his face and into his nostrils and down his neck and onto the floor and on my knees. It doesn’t matter how much I suction, the mouth keeps filling with blood.

It’s bright red, foamy. Hot. The carpet is thick with it, my knees are pressed into a pool. I hear heavier thuds in the distance – dad has found something heavier to throw.

The ALS truck gets here. They leave me on suction and mask seal with Fire working the bag, as Marge sets up for an ETT intubation. More Narcan. Mel, an A‑EMT on the primary shift with Marge, is down at the patient’s knee getting an IO to push epi. Marge gets the tube and waveform on the cap with it. Suction, suction, suction. I have to stop every 15 seconds, protocol, and any ground I gain is lost. There’s blood on my face now, in my hair.

More epi, and after two more asystole readings, brady PEA, then finally v‑fib. Shock, epi, shock, epi.

Normally, I study everything Marge does, to pre-empt her needs on future calls. I usually stash a few questions. But today it’s all background noise, with the screaming and thudding. I keep looking down at the kid, so impossibly lifeless. Blood he should have wiped away oozes into his open eye. There’s nothing in this body anymore, nothing to pilot even its most basic functions, nothing to even close its eyes. I keep suctioning. I want so desperately to be anywhere but here.

Mutual aid comes on scene from Hanover, and now we’re shouldering him down the stairs, pushing past his mom who grabs at my shirt and pants, trying for a handhold, screaming in my ear.

On route, I suction away over 500 ccs of blood. So much goddamn blood.

In the trauma room, the ED docs throw some cocktail of meds at the kid, shock him a few more times and finally get ROSC. Last I heard, the kid’s basically braindead, hooked up to just about every damn piece of equipment the ICU has.

My shift ends at 7am. I go home and take an hour-long shower where I scrub not just my hair, but every inch of my skin until it starts to hurt. I cry in there, something I had not expected when I first got in, but something I don’t bother trying to restrain.

#

After long night shifts, I like to treat myself to a nap, and usually that nap carries me all the way until the next day. But again, I’m wide awake and staring at the ceiling.

I find myself working through the nasty calls. It starts with the kid from last night and his foaming, unrelenting blood, but then it works backward, deeper. Digging.

Old calls come back, and with them bubble up details I don’t even remember processing. The suicide’s son collapsed in the couch across from her, stammering over and over about how he always keeps his firearm locked up. The one time he forgets. The one time. The Adele album playing off the overdose’s phone, muffled from the shower steam that had condensed on the speaker. The stroke reaching out and finding my hand, squeezing. He was still in there, trapped in directionless terror.

It dawns on me that I’m not in control. These are parts of my mind, I realize, that I do not visit, dare not tread across, like early-winter lake ice. Yet here I am, stepping out and testing my weight. Someone else, something else, is examining my memories, turning over rocks and looking for grubs.

A thought flashes quickly, one that is not mine. The rest of my brain rises against it, like an immune response, and tears it apart. Too slow. It hadn’t been words, it hadn’t been human. It was visceral, heavy in my guts: patient desire, hunger for something it hadn’t yet found. Salivation.

I’m left thinking about mounds of spider eggs. Of nesting.

#

“You look like dogshit,” says Marge as I come in the door. She’s sprawled on the couch, some news program muted on the TV. Marge is working a 48, and this is the start of the second 24-hour leg.

“Feel like it.” My eyes are puffy and bagged, and my skin is a clammy grey.

“Big night? I hate hangover shifts.” Marge grins and fans open a magazine.

I pause on my way to the kitchen. I don’t know how to describe what last night was like, but I don’t want to call it ‘big.’

“Wasn’t drinking,” I finally say. “Just up late.” I pour myself a cup of coffee from the pot.

“Well, to reiterate, you look like shit,” Marge says. “Go grab a nap before a tone – ”

buuuuuuhWEEEE beepbeepbeepbeepbeeepbeep

She gets to her feet with a sigh. “You better not fall asleep behind the wheel.”

I don’t, though my driving is subpar.

“You know if you’re still drunk in the morning, it’s better to call out sick,” says Marge, in a haze of sour watermelon vapor.

It’s a simple call – chest pain in a 52-year-old-male. I screw up the lead placement for the EKG and can’t get a manual blood pressure reading.

In my head, I swear I hear bells ringing.

Marge pokes her head up into the cockpit after I clear the scene over the radio. It’s a BLS call – the EKG is normal and his blood pressure is fine. On a better day we wouldn’t have had to transport at all, but the patient had requested to go to the ED. Marge had volunteered to tech the call. She doesn’t need to say it out loud – with whatever is going on with me today, I’m not getting anywhere near her patient.

“Just don’t kill us kid, alright?”

“Yes, Mom.” At least I have some sense of humor still.

My least favorite part of the whole job is driving the rig. I don’t really like driving period, not even my twice-owned Corolla – and I don’t appreciate how our truck is twice as wide and half as responsive, wheels touching both edges of the lane. This was all to say – I don’t drive quickly, especially not today.

“Some of us have plans tonight!” Marge calls. It’s as if she has a speedometer embedded in her brain.

Today, with my hallucinogenic dose of insomnia, I’m driving even slower than usual. My mind drifts, slips, to warmer, summer days. Me and Simon, swimming in the river.

Then I feel something lurch, through the gaps in my sleep-starved brain, toward something I didn’t know I was guarding. It dug in, hard, hundreds of sharp pricks drew the entirety of my attention, focused it on what this thing had found.

Simon.

Brake lights cut away my brother’s face – I’m flying up on some dinky sedan puttering away in the right lane. I lunge for the brakes – too sharp, a thump, Marge against the padded medic seat.

“Precious cargo!” Marge yells.

“Sorry,” I murmur back. I rub my eyes, shake my head, maneuver around the sedan.

I can’t settle it. It’s latched on, a tick embedded down to its neck, engorged. It’s a dull ache that demands my attention, as my mind runs in circles trying to pull it out.

I’m chasing after Simon and his friends, I want to hang out with them, but they’re too fast, and they lose me in the trails behind the park. I can hear Simon laughing somewhere. I walk back home and trash his room.

It’s the rumble strip, not brake lights, that jolts me away this time. The ambulance has slid out from its lane, the dull guardrail ahead. I could’ve drifted back onto the road had I reacted then. But for a moment, I’m not behind the wheel of the emergency vehicle, but in the backseat of a Suburban, glancing up over my Gameboy because I feel us sliding. The guardrail speeds toward me, looming. My mind widens to comprehend the force of the incoming collision…

I flail – tear myself from the memory like a mouse stuck in a glue trap might tear its own leg off. I yank the wheel, my foot pounds the brake. The ambulance swerves from its collision course, wheels whistling on the pavement. Marge is thrown against the cabinet, hard. A latch springs open and I hear gauze and tubing and whatever else spill out.

“Derek!”

#

I earn myself a week’s suspension, Marge sees to it that I’m punished. She’s loyal to her partners, until they put her patients in danger. I respect the hell out of her for that.

“Take the slap on the wrist, and shape up,” Marge says, gripping my shoulder as we leave Boss Man’s office. “This is real stuff. If you’re going to be here, be here, yeah?”

#

I still can’t sleep, and now I’m losing track of time.

My days blur into streaks of grey. I’m on my couch, in my bed, walking along Bradford’s main drag in the pitch dark. I wonder if these are dreams. I read the Wikipedia entry for Schizophrenia.

The suckling keeps my brain on though it desperately wants to turn off, an insistent pain that won’t let me rest. It holds me in hell, in those quiet days and years after the crash, after the funeral.

Dad turns to the liquor store. He hides it for a while, burying his empty fifths deep in the trash and later, the basement crawlspace when there are enough to fill the bin. Eventually, he stops caring enough to hide it. Mom returns to cigarettes – she had quit before her pregnancies – and does puzzles out on the porch, even in the winter when it’s cold enough to freeze your snot. Smoking inside is a line she won’t cross. They’ll split a few years later. It’ll help Mom, a little.

That thing is swollen, puffed up and enveloping the whole memory. Still it feeds, greedy, tearing.

I’m in the Suburban.

Here, it goes on forever. The guardrail looms, the anticipation of collision is thick in my throat. Horrific inevitability. I’m frozen, every muscle fiber already tensed. And the realization, the one that had only blinked on the day, is now branded to my frontal lobe. There is nowhere else to look.

Simon is in eighth grade, rebellion in full swing.

“Seatbelts are for pussies,” he boasts, chin raised.

Mom makes him put it on when we first all load up, but once she turns back around in the passenger seat, Simon slowly undoes the latch, quietly, so she doesn’t hear. I watch him. Simon winks. I keep my mouth shut.

Everything else in my brain is shut down, the emergency stores are barren. I’m stuck here, stuck squirming away from this throbbing agony in my head, stuck in my nightmare.

No, not stuck. Held. This thing likes it better when I watch.

#

Something’s burning.

I don’t remember getting out of the Suburban, but here I am standing next to it. The front of the car is gone into a crumpled mess of metal and plastic where it’s impossible to tell what’s vehicle and what’s guardrail. It’s smoking, hissing, red fluid spraying out onto the snow, like the car is bleeding. The windshield is limp, folded, webbed into hundreds of geometric subsections. It’s punched open near the middle, a flap of glass yawns out into the tangle of debris.

I’ll later spend a large stretch of time in the PICU, recovering from a fractured lumbar spine, lacerated spleen and liver, and the subsequent surgeries I’ll need to get everything patched up. I don’t feel anything now though, there’s a numbness over me. A glaze. I step toward the car, glass breaking under my toes. I see my parents through the hole in the windshield, unresponsive on the airbags. Mom is smeared red.

And then my eyes settle on Simon’s seat. Empty. I know then what’s happened, I put it together in an instant, but I swat it away on impulse. I’m wrong. I must be wrong.

There’s something in the right-hand lane, still and bent and broken. I inch toward it. There’s a streak leading to the shape, dark in the harsh light, like ink.

I step out closer.

This is where the memory ends.

There are pieces missing. It’s hard to figure out what, but I know there isn’t enough there for a whole body.

I don’t remember anything more. I’m lucky for that.

One of Simon’s legs is kinked at an odd angle, like the kickstand on his bike.

Christ, this is where the memory ends!

Simon is face-up. Probably. I think I can see the nose. Most of the skin has been shorn off on the asphalt.

I pull away, as hard as I can. Some part of my mind has wrapped around this thing that has buried itself in the horrors of my brother’s corpse, and it tears free. Ripping. Smashed spider eggs. A swarm explodes over my brain in a cacophony of stimuli – sobs and screams and blood and bone and bells. My body, wherever that is, manages a feeble yelp and I’m swallowed in black.

#

I come to and my head is quiet, for the first time since I’d heard those damn bells. I’m in my bed, in a puddle of stale sweat. I’m starving. I have to piss.

Then my front door opens – the rusted hinge I’d been meaning to WD40 for about three months now whines.

“Derek!”

My blood runs cold. I know that voice. It’s one I haven’t heard since a ill-fated family snowshoe outing. I try to sit up, to turn to face him, but I’m locked to my bed. Paralyzed.

Footsteps, louder. Uneven, gaited, dragging. Leg like a kickstand. The knob on the bedroom door rattles, the door slides forward over the carpeting. When they slid the spatula beneath him, his upper back and neck had slunk like a wet noodle, moving not as one but as some pulverized gel. I imagine my brother walking toward me now, head lolling on a structureless frame. Shuffling. I try to close my eyes but they’re fixed open, up to the ceiling.

“Derek,” he calls again, softer this time, in that pinched pubescent voice. He pads across the room, softly now. No! I want to shout. No, no, NO! but my vocal cords are stone. I don’t want to know. I don’t want to see. I want Simon’s body to stay buried deep in the cobwebbed crawlspace of my memory, underneath mounds of other forgotten junk. Why had I kept it at all?

“Derek,” Simon says again, this time right beside my ear. I can feel warm breath on my cheek. My heart pounds in my neck, my breaths come in ragged clutches. I want to twist away, to squirm backwards against the wall, to buy myself every centimeter I can, but I’m stuck. Not just here, in my bedroom – I’m kneeling out on the highway.

“You know it’s not me, Derek,” it says, hardly above a whisper. “You know it’s not Simon.”

I croak out what was meant to be a scream. I thrash against my paralysis, but the best I can do is twitch my fingers.

“You know it’s not Simon, Derek.” Louder this time.

Sweat breaks out over my brow. A drop runs into my open eye, stinging, blurring his vision. I should wipe it away.

“You know it’s not me, Derek. You know it’s not Simon!” The voice builds to a yell. I can’t pull my head away from it.

“I’M NOT SIMON, DEREK! YOU KNOW IT’S NOT ME!”

My ears ring from the sudden bellow.

“I’M NOT SIMON! SIMON IS DEAD! YOU KNOW, YOU WERE THERE! YOU WERE THERE, DEREK! YOU SAW THEM SCRAPE HIM UP!”

My throat tightens into a straw I can hardly breathe through. Not-Simon’s voice drops low again. “Do you want to see? Do you want to know what he looked like?” It pauses, breathing into my ear. I can smell the burning, the blood. I want to shake my head. I want to scream. “I don’t need to show you though, do I? You remember, Derek. You were there. You saw.”

I had seen, and now I remember.

Simon is splayed out on the road. Bits that had once been an arm are splattered on the highway like clumps of Jell‑O. His neck is bent like a crinkle straw, kinked and bulging at new joints. His face, stripped of skin and fractured in a thousand places, crumpled like a red napkin.

My eyes lock sideways, pressing hard against the ends of their sockets, set not on the peeling wall beside me, but on the twitching somewhere in the mess of gore, a muscle still firing, a neuron cracking off a few more pulses. Some part of Simon still in there, trapped.

My vision greys. My muscles stiffened and my jaw peels open.

Seizure.

It moves. It oozes through my ear, pooling down through my sinuses like sludge. It gathers at the base of my throat, bubbling like a brewing potion.

Is this a goddamn stroke?

Why can I still think? Why can I still feel?

The sludge slides up my throat, as if gravity has been switched. My jaw forces open wider, my neck and cheek muscles strained. God, they feel like they’re ripping. My vision darkens even deeper, a static falling over his room.

It emerges.

Legs bloom from between my lips, bend and plant themselves on the taut skin of my face. Thin, hairy, insect legs, with little barbs that draw dribbles of blood from where they land. Ten of them, no, a hundred. More and more pop free as I watch. They push and push and my head is shoved into my pillow, and then its body is sliding free. It’s warm and wet with something thick, like congealed blood, and it has short and spiky hairs that scratch up my gums. It twists and wriggles to get free of my teeth, and then it’s out.

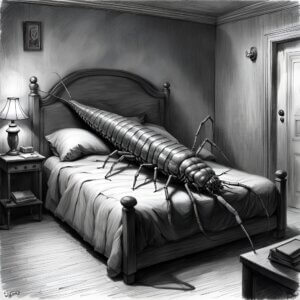

My arm involuntarily pounds the side of my bed, my jaw aches against its mechanical restraints, my eyes shake and blur. It turns, its legs tapping in long waves like a centipede, and it comes toward me.

Unconsciousness seizes me, finally, but not before I catch a glimpse. It has plating along its back, up to its head where the last piece curves over like a samurai’s helmet. Thorny antennae uncurl from the shadows beneath its faceplate, tapering on and on to impossibly long points, twitching toward my face.

My vision is fading, so I can’t be sure, but the antennae look blurred, as if rippled in shadows. As if they’re covered in a swarm of tiny, black mites.

It’s Hanover, not Baker Valley Ambulance, that responds to the motor vehicle versus pedestrian call off the I‑89 overpass toward Enfield, but word reaches the station regardless. It was grizzly, Marge hears, the kid threw himself in the path of an 18-wheeler, and got scrambled pretty good. It was an obvious DOA.

One of the paramedics had needed to jog back to the rig, in search of an orange backboard.

David Vonderheide (he/him) is a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania. He spends his summers outdoors, working as a whitewater raft guide. His work lives on davidvonderheidewriting.com.