It was still back there.

James spotted it as soon as he squatted at the top of the ridge. The men below him grunted, sweating with the effort of lifting their canoe over a pile of rocks. His own group had already reached the top and paused for a moment of rest before they began the equally arduous task of carefully lowering the boat down the other side.

“Still there?” asked Samuel, taking a seat on a rock nearby. James nodded. Samuel took a piece of salt pork out of his pack and held it between his teeth, sucking on it loudly and smacking his lips in a way that made James want to push him off the ridge. James clenched his fists, the nails biting into his palms. They were two months into their voyage, and the days were wearing on him hard.

“Should we tell ‘em?” asked Samuel. James watched as the salt pork was maneuvered expertly, firmly tucked into one cheek like a piece of chaw.

“How are we supposed to do that?” said Lewis, who wandered over to join them.

“Shout or somethin’?”

“They won’t be able to understand you,” said James. “They’ll notice it soon enough.”

“You thinkin’ it’s an Indian?” Samuel switched the pork from one side of his mouth to the other, irritating James again. He wanted to take the man and shake him, shout swallow it already into his face, but James held back. Only a few more days and they’d be back on the Mackenzie River, and not long after that they’d get to Fort McPherson, where Hannah was waiting for him.

“I don’t think so. Gwich’n often work with the Company, I don’t think they’d be sneaking up behind them like that,” James said.

The figure had appeared seemingly out of nowhere, first a half mile or so behind the group, then creeping ever closer to the man at the back. It was John Thornton from the looks of it. Difficult to tell one person from the next at this distance, but John towered over most men and was easier to pick out of the group.

Where it came from, James couldn’t say. Not many people lived up here in the Yukon. The ones that did stuck close to the forts and trading posts in the area, lest they disappear quietly into the darkness that waited at the edge of their doorstep. The Yukon wasn’t like what all those folks on the Trail were facing out west, no sir. This land was feral. It took its pick of anyone who strayed too far from the path.

“What do you think he wants?” Lewis asked.

“Don’t know. Maybe food.” But even as James said it, he knew it wasn’t right. The shape moved too quickly to be someone starving. Even from here, the steps looked confident. The figure had exaggerated strides that easily cleared the sedge and chunky rocks that littered the terrain below.

“Maybe he got hisself lost,” said Samuel.

“Maybe,” said James, doubtful. The men watched in silence as the shape grew closer to John. The young man was likely focused on where to place his feet, distracted by the effort it took to carry the canoe over uneven ground. James had lost count of how many times they had to portage this trip, each occurrence eating up precious time and energy on their way from Hudson’s Bay to the Peel River. If there was an easier route between the two areas, it had yet to be discovered in 1848. Not by John Bell, not by Alexander Murray, not by any of the other explorers on the pursuit of hunting grounds or the Northwest Passage. There was just no way around months of hard work. This was James’ fourth trip, and each time he prayed a little harder that it was the last.

An eagle screamed above. James watched it fly in the sunlight. It was June, but it wouldn’t be long before the daylight was gone for good and the cold blanket of winter was upon them. Hannah hated the winters here, had ever since they married and she came to the Yukon two years ago. By the time winter broke and the sun began to lighten the horizon for a few hours each day, she was practically climbing the walls to get away from it. Hannah said she wasn’t terrified of the dark itself, but the dangers that could hide within it. James didn’t really understand the difference.

“Look!” Samuel pointed. The men below had paused and lowered the canoe onto a bit of flat ground. John was wiping his brow and surveying the land behind him when he spotted the figure. James and the other men could hear him call out as he pointed frantically. It was only ten or so feet behind the group, strutting up behind them.

The shape, which was human in nature, looked as if it folded in half suddenly, the torso leaned forward and reaching. It stretched impossibly long arms out ahead and barreled toward John, the tall man tripping over his own feet as he scrambled back. The shape was on him in a moment. His strangled screams carried easily along the chilly wind that never seemed to cease out here.

“What the hell!” said Lewis. He and Samuel started down the slope to help, but James hung back a moment, too horrified to move.

Was it a bear? A cat? No, he was sure it had walked upright, its cadence even and arms swinging like a man. But the way it collapsed and stretched towards John made James unsure. He hurried after the others, dashing toward where the screams were escalating. It was a frantic noise that sounded like the slaughter of pigs.

I wish I was home, thought James. A vision of Hannah in her plaid skirt, a basket of wildflowers hanging off one arm came to him. Happy and healthy in the sun, the lake behind their house glinting.

A small dip in the path put the other group temporarily out of sight. James climbed up out of it and bumped into the back of Samuel, motionless at the top. The whole group was frozen at the scene laid below.

The canoe, carefully borne and paddled over thousands of miles, lay tipped on its side. Bodies were strewn around it, limbs tossed, throats torn, bellies opened to deposit steaming piles of gray entrails on the dirt. The ground drank up the blood, the unnaturally dry summer leaving the land thirsty for every bit of moisture it could find.

Beads of sweat at the edge of James’ scalp united and ran down his face and neck. He could hear Samuel sucking on that goddamn salt pork again, but when he turned to look, Samuel’s face was still and his cheek was empty. The sound was coming from somewhere beyond the group, and when James looked towards it, he saw the thing crouched and suckling on the end of a leg, licking and nibbling delicately at the broken femur it gripped in its hand.

Swallow it already, thought James. For goddsakes.

The foot flopped lamely about on the end and James noticed the shoe had a hole in the toe, the product of all the miles the men had traveled so far. The creature set the leg carefully on the ground and tilted its head up to the sky, shrieking.

It was human, in a way that suggested the creator had only seen people from afar and was a little unclear on the details. The arms and legs were too long, the head tiny. The torso began as a narrow waist and expanded into a knobby ribcage, points of bone stretching the skin beneath almost to the point of ripping. James spied small, pointed teeth, the rest of the face and head an amalgamation of ridges and shiny skin. He had once seen a drawing of a devil in a book, shaped much like this. But while that devil was red, this thing was deep green and brown, the color of a rotting log hidden deep in the woods.

The creature looked up with bright white eyes too big for the face. It scampered toward them on all fours, quicker than anything James had ever seen.

Samuel ran. Lewis stood his ground but threw his arms up in defense, forearms covering his face. The other men set to scrabbling like frightened dogs on a slick floor, tripping and pulling each other down in an attempt to get away. There was gunfire off James’ left shoulder, a flurry of shots that dropped a man caught in the path. James backed up. When the creature turned to him, he dove for the canoe and pulled it down, the boat settling to the ground around him with a comforting thump.

Outside there were muffled grunts and thuds. Twice a shot rang out and then there was a yelp, followed by ear-splitting screams that ended abruptly. Too quickly, there was silence, heavy in the air as an autumn fog.

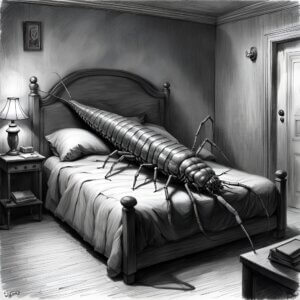

The air under the canoe grew stifling; It was warmed by James’ breath and humid from his sweat. He could feel the ground underneath him was muddied and slick, made worse when he pissed himself as the men died around him. There was little room for anything and he began to feel panicked as he lay on his belly in the small space; his muscles cramped and his feet tingled and he shifted quietly in the mud trying to relieve the pressure and told himself over and over it wasn’t a coffin although it really did feel like one. Every time he moved basted himself in Yukon soil. The earthy smell seeped into his pores and the coarse dirt penetrated into every crevice and nook of him.

James felt dirty and he loathed the sensation. He longed for the lake and its cool waters, to slip into it bare like he and Hannah did sometimes in the moonlight.

Hannah, he thought. Suddenly he understood. The dark of the canoe didn’t frighten him, but what the thing outside could do inside of the darkness, that gripped his heart so tight it ached every time it thumped against his chest.

An hour went by, maybe two after the noises had ceased. It was difficult to get a sense of time as he lay curled up in the dark. His stomach began to growl and his legs ached in earnest. He could not live under that canoe forever, so he put his back up against it and tilted it as slowly and carefully as one raised a sleeping babe.

This far north, the sun would only bounce against the horizon before rising into the sky again. James could see it was just beginning its climb back up. He wished for the dark. It was light enough to see the destruction around him, the way the ground had been torn up, bushes snapped and the grass crushed as the men fought back. His heart dropped as the pink light showed Samuel’s face. It was heavy-lidded and surprised at its own dislocation from the body lying ten feet away. Lewis was facedown thankfully. James could tell it was him from the buffalo hide jacket. Lewis’ shoulders were both ragged stumps where gristle and fat and clean white bone showed through the chaos.

A clicking noise came from the small stand of trees to his left and James’ head snapped to it. The creature eased itself out of the shadows. James looked about but was too far to make it back to the canoe, not with how fast it moved. It chittered as it slunk closer to him and he felt his bowels loosen as it reached one gangly limb out. He dropped his eyes to the ground and fought the urge to run as the other men had.

A ragged claw touched his cheek. It was a thickened, sickly fingernail, ridged and bumpy, ending in a point that scratched at him and flaked off a bit of the mud that had collected there. James felt it scrape his cheek underneath the dirt. The skin was raw and burned where it touched.

The creature backed up and popped its jaw like a bear. The noise was a deep click that resonated inside his chest. James cowered, too scared to do anything but stand there and hold his breath. Two feet, elongated and with curled toes, stepped toward him. The thing bent and sniffed his head and whoofed, the hot breath damp on his already sweaty neck. In a moment, he knew that mouth would close around his head, those tiny pointed teeth piercing his temples as it crushed his skull in its jaw.

There was a noise from the woods, a quick rustle of branches followed by a high-pitched shriek. The creature beside him answered and James flinched. It clicked once more and then was gone, leaving the scent of rotted meat and decomposing leaves in its wake.

James collapsed, curling into a safe little ball, rocked forward on his heels and shivering. He stayed down until his legs began to scream and a nighthawk called out over him. Whatever the thing was, it was gone. Everyone was gone. He stood slowly. The wind caressed him, the sensation dulled by the layer of mud that covered his skin. He moved forward, stepping over the bodies of the men he had sweated next to for the last few months. It smelled ancient around him, like an old battlefield in a forest. Even now he could see the scavengers lying in wait, the shiny crows with cocked heads and a little gray fox, prowling around the edges of this tragedy.

James moved slowly back up the ridge, lumbering heavy on wooden legs. He was so tired all of a sudden, exhausted and dirty and numb. His whole body was heavy and his mind struggled through a thick fog that seemed to seep out from his ears and run down his face. He could smell it and taste it at the edges of his mouth, salty and foul on his tongue and running down the back of his throat. He gagged and then stood up, his vision swimming. He didn’t want to be here anymore. He wanted the thick straw mattress and the rosy-cheeked woman whose name he couldn’t quite recall, expecting him just a few days’ journey away.Home, he thought, as he itched at his face with a dirty nail. That’s what I want. He felt a burst of vigor at the idea of it, suddenly feverish with his want. James strode forward. He climbed the ridge and descended into the dark woods, pushing past branches and ignoring the clicking that echoed against the mossy trees around him. He was headed west, to a cool lake and a field of sweet wildflowers, to where Hannah waited in the house alone.

Anne Woods (she/her) loves all things spooky. When she is not writing horror or falling in love with a new book, she can be found tending her garden and having loud arguments with her orange tabby cat, Franklin.